Migiziwazison Foundation is always ready to help create food and medicine gardens at schools and other corporate or institutional settings. It sounds lovely, right? Many groups have received grants and been given prominent locations for the project. But the reality is that a traditional Native garden in this region is not going to ‘look good’ all season long. And somebody is bound to get upset about this truly natural reality.

Non-Native aesthetic ‘norms’ are historically rooted in long-standing environmentally harmful practices, and this often causes tension or outright conflict between those creating & caring for this type of garden and those running the school.

Every year, we spend a fair amount of time trying to convince everyone from superintendents to principals to facilities and groundskeepers that what they think is a ‘weed’ is really a plant relative who has a lot to offer human beings. That we will not be “deadheading” or tilling the soil regularly. That dead plant material will be left where it falls so it can decompose and return its nutrients to the soil while providing habitat for fungi and beneficial insects. And that while this looks “bad” to some, to those who are educated on how this particular part of Turtle Island functions, it’s beautiful. As always, we seek to reduce conflict by helping people understand the fundamental difference in perspectives comes from very different historical relationships to what a “garden” is supposed to look like and what it’s function is.

Do you know where the whole idea of landscaping and front-of-the-building gardens originated in this country? Answer: the European aristocracy. To demonstrate their wealth and power, aristocratic families took land that used to grow food and medicine, and made it purely decorative. Everyone else simply mimicked this ego-centric practice in an effort to appear more wealthy and powerful themselves. Only the poor on farms or in cottages used every square inch to grow their own food and medicinal plants.

So what looks ‘nice’ or ‘beautiful‘ in terms of a garden has been warped into an entirely unnatural set of harmful practices. The result is a demand for landscaping that are truly alien: Lawns that are simply a monoculture of typically imported grasses. Hybridized flowers that cannot reproduce without human intervention (because no natural pollinators exist). Invasive species like bellflower, Asian bittersweet, and buckthorn that escape gardens and crowd out native vegetation.

To support these aliens, facilities use chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Tilling the soil every season is also common, so the soil is further depleted, it’s structure and living organisms destroyed, and more chemicals are needed to maintain this foreign notion of what is ‘a pretty’ garden.

In short: the typical institutional landscaping in the upper Midwest is a perfect, hyper-local example of the general belief systems and dominant cultural norms based on foreign (to this region) practices, that have caused planet-wide water, soil and air pollution, and threatens pollinator populations critical to our food supply.

In this area, Indigenous people practice ’soft touch’ agriculture. We discourage the plants that are not useful to us (or are not key to keeping high populations of the animals we eat). We encourage or propagate food and medicine plants. All the stories you learned in grade school about the ‘land of plenty’ that greeted colonizers are proof of how well Indigenous land practices worked for hundreds of years. All that ‘plenty’ was no accident. But it wasn’t “pretty” if you look at it through the eyes of someone trained to see beauty in the unnatural.

Native gardens will look messy to non-Natives or other untrained humans. Beyond the fact that most Europeans have never bothered to learn what gifts native plant ‘weeds’ have to offer, keeping indigenous plants going & increasing year-after year doesn’t always look ‘pretty’ to the uneducated. Not all plants we commonly use are true perennials. We must leave dead plants standing so the seed heads fully mature and the seeds fall to the ground at the right time, so next year’s blooms will happen. Some of these dead plants are hosts to the larvae of important pollinators (like moths and butterflies) that burrow into the stems to survive winter. We cannot clear the dead plants right away in the spring without killing them. And without pollinators (some plants have only ONE insect species that does the job) again, no new plants.

I have dozens of more examples I could share about how cultural differences result in plant bigotry. I don’t use that word lightly.

For generations, non-Native people have been killing off the very plant relatives that have supported humans on this continent for centuries. You only have to look at the massive reduction in wild rice available in lakes and rivers to see hard proof. Locate “Rice Creek Chain of Lakes” on any map of Minnesota. Wild rice used to be plentiful from that area all the way north of Mille Lacs lake, to where it still grows today (and continues to be under serious threat from land practices that degrade water quality and climate change-caused droughts and floods).

Set Expectations Early & Reinforce them Often

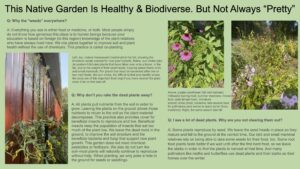

If you are involved in a project to create Native gardens, be prepared for the inevitable conflict. Hold meetings early and often to educate everyone in leadership roles and bring the folks responsible for keeping the grounds on board. A great idea is to create signage that educates visitors on what a naturally biodiverse, healthy garden should look like throughout the growing season in your region. I’ve attached a helpful image for that at the end of this post. This sample sign explains specific practices in very brief ways, showing pictures of the same areas in Migiziwazison-tended gardens at different times of the year. Feel free to use and/or modify it for your purposes.

Thanks for listening. Enjoy your naturally beautiful medicine gardens even when they are half-dead. Mi’iw.

Feel free to use these images and the language of this sample sign in your own Native garden. Contact us for a file you can use to customize this sign and create a high-resolution image.